TECHNOLOGY

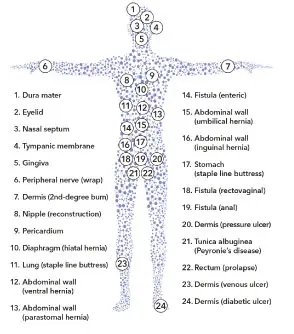

Nexsis Biosciences™ develops and delivers advanced tissue-repair products from biomaterials that contain a naturally occurring extracellular matrix (ECM).

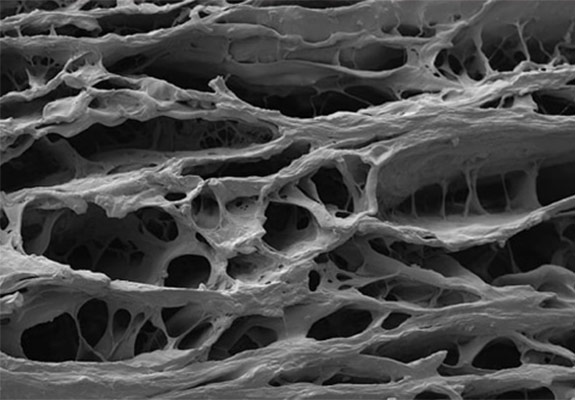

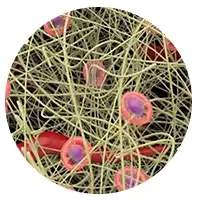

High magnification SIS image

ECM's Role in Tissue Repair

ECM is the structural and functional material that surrounds cells in nearly all body tissue. It serves as the support structure upon which cells orient and move in response to other cells and signals and provides a healthy environment necessary for tissue maintenance and repair.1

Tissue-repair processes occur through the coordinated activity of cells that reside within the ECM. Because the ECM is necessary for tissue maintenance, it also plays a major role in tissue repair.1 Without a functional ECM, the body can no longer support normal cellular processes, and tissue repair fails to progress.2

ECM Composition and Function

Various components of the ECM play vital roles in supporting cell function. While the composition of the ECM varies by tissue, there are generally four groups of components:

| ECM COMPONENTS | EXAMPLES | MAJOR ROLE IN THE ECM (Ref. 3-10) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural proteins | Collagen, elastin | Facilitate cell guidance and migration; provide mechanical structure and support |

| Glycoproteins | Fibronectin | Facilitate cell binding and migration |

| Glycosaminoglycans | Heparin, hyaluronic acid | Bind growth factors; mediate cell adhesion and proliferation |

| Proteoglycans | Heperan sulfate proteoglycan | Moisture control |

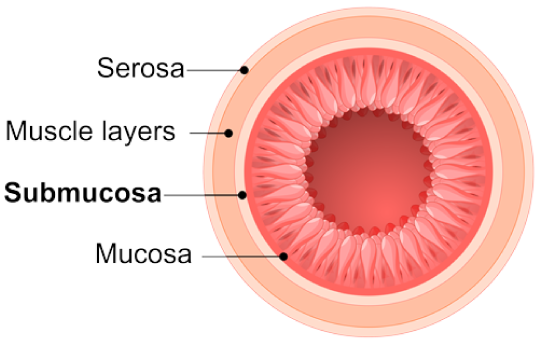

SMALL INTESTINAL SUBMUCOSA (SIS) PRODUCTS

Nexsis Biosciences’s SIS products are biologic grafts made from a byproduct of the food supply chain, a highly regulated industry that ensures a high level of consumer and product safety.

SIS material is obtained from the intestine in a manner that removes all viable cells, but leaves the naturally fibrous and porous nature of the matrix behind.11 These proprietary processing methods retain the complex architecture and composition of the extracellular matrix, providing not only the structural collagen framework but also the natural non-collagenous ECM components that are essential for cell interaction, function, and ingrowth.11,12

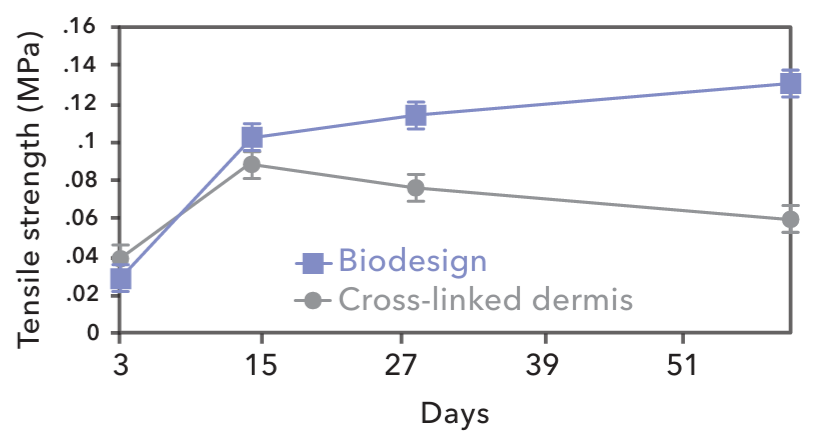

Because they are not chemically cross-linked during the careful treatment process, SIS grafts provide a natural scaffold that allows the body to restore itself through site-specific tissue remodeling. As healing occurs, SIS grafts initially act as scaffold material to support the population of the ECM with patient-derived cells. Over time, SIS grafts are gradually remodeled and integrated into the body, leaving behind organized patient tissue that provides long-term strength.13-15 Chemicals used to cross-link grafts can release cytotoxic residues and provoke encapsulation. However, SIS grafts are not cytotoxic, are resistant to infection and encapsulation and become strong, vascularized tissue that functions naturally.1 As shown in the chart, SIS grafts result in a repair that becomes stronger over time.16

Strength of incorporation of explanted grafts. Days post-implantation vs. tensile strength in megapascales (MPs). Error bars = SEM, n=616

OVER 6,000,000 SUCCESSFUL SIS IMPLANTS WORLDWIDE.

TISSUE REMODELING

Tissue remodeling is a complex natural process that involves the recruitment of cells, the renewal of tissue composition, and the reinforcement of structural tissue architecture.17 As the body heals, SIS is gradually remodeled and integrated into the body, leaving behind organized tissue that provides long-term strength.13-15

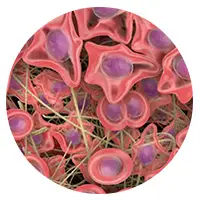

RECRUIT

Immediately after implantation, the remodeling process starts when the body’s Inflammatory and progenitor cells populate the matrix and release cytokines and growth factors that recruit collagen-secreting fibroblasts.18,19 In this phase, SIS acts as a scaffold material to support the population of the ECM with patient-derived cells.

RENEW

As remodeling progresses, host macrophages and fibroblasts in the newly populated matrix work together to renew the tissue through the complementary processes of phagocytosis, collagen deposition, and angiogenesis (blood vessel formation).20 In this phase, SIS is gradually replaced by the patient’s own tissue and cells.

REINFORCE

Over time, the resident fibroblasts secrete cytokines and growth factors to signal reinforcement of the deposited tissue through the processes of additional collagen deposition and maturation, resulting in a strong, repaired tissue.12-15 In this phase, SIS is no longer needed as the patient’s own collagen has gradually matured into a stable structure that has long-term strength but is entirely the patient’s own.13-15

PROPRIETARY MANUFACTURING PROCESS

Cook Biotech (now a part of Evergen) develops and continuously improves proprietary processing methods to adapt SIS for specific clinical applications. The result of the these proprietary processes are variations of SIS that are optimized for application-specific requirements, such as strength and biochemical attributes. During manufacturing, SIS material is obtained from the intestine in a manner that removes all viable cells but leaves the naturally fibrous nature of the matrix behind.

The complex architecture and composition of the ECM are retained, providing not only the structural collagen framework but also the natural non-collagenous ECM components that are essential for cell interaction, function, and growth.11,12 Each product is then meticulously crafted to meet global quality standards with SIS material that was processed specifically for the product’s clinical application.

REFERENCES

Images sourced from cookbiotech.com unless otherwise noted

1. Clause KC, Barker TH. Extracellular matrix signaling in morphogenesis and repair. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(5):830-833.

2. Daley WP, Peters SB, Larsen M. Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 3):255-264.

3. McPherson JM, Piez KA. Collagen in dermal wound repair. In: Clark RAF, Henson PM, eds. The molecular and cellular biology of wound repair. New York: Plenum Press: 1988:471-496.

4. Raman R, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Structural insights into biological roles of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Chem Biol. 2005;12(3):267-277.

5. Sottile J, Hocking DC. Fibronectin polymerization regulates the composition and stability of extracellular matrix fibrils and cell-matrix adhesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(10):3546-3559.

6. Kristensen JH, Thorlacius-Ussing J, Ronnow SR, Karsdal MA. Elastin. In: Karsdal MA ed. Biochemistry of Collagens, Laminins and Elastin. 2nd ed. London: Academic Press: 2019:265-273.

7. Almond A. Hyaluronan. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(13):1591-1596.

8. Rizzino A. Transforming growth factor-beta: multiple effects on cell differentiation and extracellular matrices. Dev Biol. 1988;130(2):411-422.

9. Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(7). pii:a004952.

10. Stringer SE. The role of heparan sulphate proteoglycans in angiogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 3):451-453.

11. Hodde J, Janis A, Ernst D, Zopf D, Sherman D, Johnson C. Effects of sterilization on an extracellular matrix scaffold: Part I. Composition and matrix architecture. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18(4):537-543.

12. Nihsen ES, Johnson CE, Hiles MC. Bioactivity of small intestinal submucosa and oxidized regenerated cellulose/collagen. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2008;21(10):479-486.

13. Franklin ME Jr, Trevino JM, Portillo G, Vela I, Glass JL, Gonzalez JJ. The use of porcine small intestinal submucosa as a prosthetic material for laparoscopic hernia repair in infected and potentially contaminated field: a long term follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(9):1941-1946.

14. Stelly M, Stelly TC. Histology of CorMatrix bioscaffold 5 years after pericardial closure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(5):e127-e129.

15. Badylak S, Kokini K, Tullius B, Whitson B. Strength over time of a resorbable bioscaffold for body wall repair in a dog model. J Surg Res. 2001;99(2):282-287.

16. Ayubi FS, Armstrong PJ, Mattia MS, Parker DM. Abdominal Wall Herina Repair: a comparison of Permacol and Surgisis grafts in a rat hernia model. Hernia. 2008; 12:(4): 373-378.

17. Turner NJ, Badylak SF. Biologic scaffolds for musculotendinous tissue repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2013;25:130-143.

18. Badylak SF, Park K, Peppas N, McCabe G, Yoder M. Marrow-derived cells populate scaffolds composed of xenogeneic extracellular matrix. Exp Hematol. 2001;29(11):1310-1318.

19. Hodde J. Extracellular matrix as a bioactive material for soft tissue reconstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(12):1096-1100.

20. Badylak SF. The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Sem Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13(5):377-383.